So go ahead, be SOFT.

So go ahead, be SOFT.

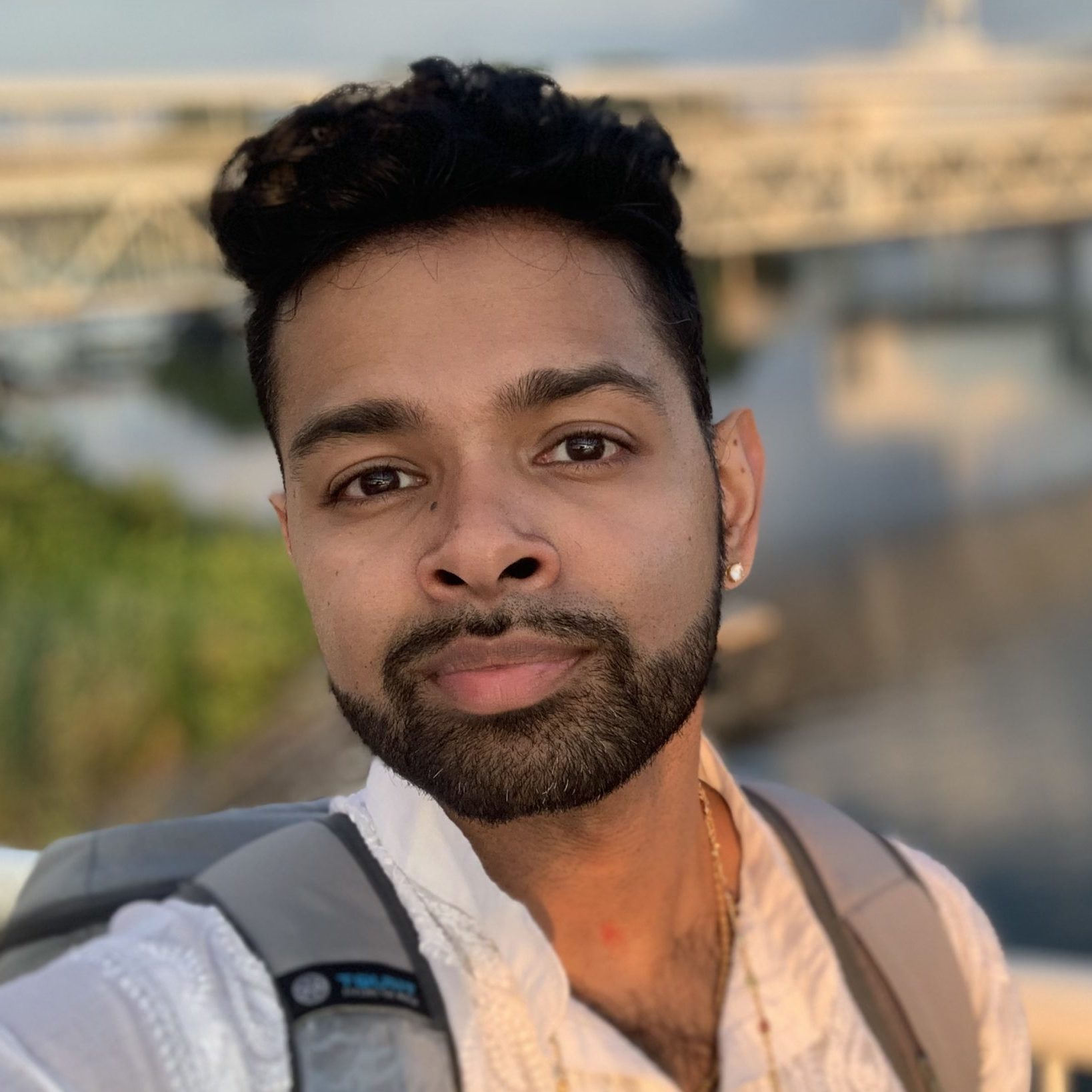

Vijay Saravanamuthu

Beyond Bullying Project

Research Assistant

Vijay Saravanamuthu

Beyond Bullying Project

Research Assistant“Don’t be such a sissy!”

I can still feel those words ringing through my mind as I think back to my time in high school. I grew up in Scarborough, and like many of my peers at 16, I wanted to be known but was afraid of being noticed. I had curly black hair that hung almost down to my shoulders, a stubbly beard that I shaped into a neat line-up and wide eyes that, despite my curiosity about the world around me, usually stared at the ground. From the outside, I was the perfect vision of a brown boy. Baggy pants: check. Athletic backpack: check. Pristine high tops: check.

Inside, my softness was suffocating.

Being gay in high school meant that one by one, all of the boys that I played handball with when we were kids pretended we were strangers when we passed each other in the halls. It meant that the boys who used to walk home with me after school now uttered “faggot” under their breath while I stood at my locker. It meant that when teachers paired me up with any boy in class for group projects, I did all the work in exchange for a moment’s mercy, to build one more ally who wouldn’t shame me on the schoolground just for being me. I always forced one foot steadily in front of the other when I walked, conscious not to sway. I wore loose clothes so no one would notice that my hips curved outwards. I avoided school dances and went home for lunch hoping no one would see me. But it didn’t help.

“Pass the Ball . . . not like that! Aww c’mon. Why do you suck so much?!” Having physically matured faster than most of the other boys in my grade, I was taller, faster, and arguably stronger. And yet, I couldn’t for the life of me find the idea of dribbling a ball around the gym to be the least bit interesting. My skills and strength didn’t shine through on the ball court, soccer field or baseball diamond. Although my cotton-candy mannerisms were policed most places I went, I dreaded gym class the most. It was the one place that the fairy magic I conjured up had no power. All my witty banter, super-sharp come backs and hair splittingly-precise comedic timing couldn’t shield me from being told that I was too weak. Too careful. Too soft. I hated high school because high school told me that I should hate myself. And, a lot of the time I did.

This isn’t one of those stories where I reach deep within and find my inner ball player. As the years went by, I never grew into a more masculine, more rough-and-tough me. I still don’t really know why people celebrate hand-eye coordination as an achievement. But what has changed for me is that I met other people. In community spaces, in the gay village, and online, I eventually met other soft souls like me. They were thoughtful, had their own struggles, and dared to be different while being seen. I made friends that looked me in the eyes when we spoke and who taught me that touch can be healing. As my world became larger and I began to meet other queers that also didn’t fit neatly into society’s check boxes of what they should look, act and be like, I found people that reflected an image of me back to myself that was radiant. I began a journey towards loving myself that I never thought possible when I was in high school. My gentle, cloud-like nature wasn’t just noticed, it was celebrated.

My softness has helped my brother see a possibility of manliness that isn’t focused on his shortcomings.

My softness has helped my mother understand that as her gay son, I want to build a world that celebrates my life’s work, and hers too.

My softness has helped young people in my life learn and appreciate new ways of exploring the world that stem from love, and not fear, punishment or exclusion.

My softness has allowed my partner to know that in tough moments, when we aren’t able to be our best selves, I will still be around to talk through our pain afterwards.

And most of all, my softness, time and time again, shows up for me as a reminder that it’s ok to make mistakes. And that I am not any less worthy of love because sometimes I mess up.

Softness isn’t weakness. In fact, it’s what the world needs more of. The problem is that like fairy magic, four-leaf clovers, and Easter eggs the power of being soft is a well-hidden secret. I can’t go back in time and tell 16-year-old me about this hidden treasure. But if you are reading this, I can tell you. So go ahead, be SOFT. It’s a gift.

Photo by Emilio Guzman on Unsplash

The booth, now festooned with banners, rainbows, and an impromptu chalkboard, became a place to hang out, eat lunch, avoid class, and share stories. Halfway through our stay at West High and we had already easily collected over 50 stories

The booth, now festooned with banners, rainbows, and an impromptu chalkboard, became a place to hang out, eat lunch, avoid class, and share stories. Halfway through our stay at West High and we had already easily collected over 50 stories